With spring approaching, running season is just around the corner. Whether you are about to start training for your first marathon or thinking of starting to run for the first time; the thought of getting an injury is always in the back of the mind. A running related injury has the potential to completely derail training plans or even become a severe injury. The goal of this blog post is to introduce a variety of simple exercises that can help reduce the likelihood of getting hurt.

What Is a Running Related Injury?

Running related injuries (RRI) are incredibly common. Up to 25% of all runners have a RRI injury at any time. The majority of all RRIs are due to overuse; when a tissue is repetitively loaded beyond what it can adapt to. Some of the most common overuse injuries are:

- Patellar Femoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS)/ Runner’s Knee

- Knee pain around or behind the kneecap (patella) that is worsened when load bearing with a bent knee.

- Inflammation of a variety of structures surrounding the knee.

- Achilles Tendinopathy

- Pain in the back of the heel or in the distal part of the calf. In other words, along the Achilles tendon which attaches the calf muscles to the heel bone.

- Inflammation of the Achilles tendon

- Plantar Fasciitis

- Heel and foot pain along the sole of the foot.

- Inflammation and degradation of the plantar fascia

- Iliotibial band syndrome

- Pain along the outside of the knee

- Compression of the iliotibial band against the lateral epicondyle of the femur.

Acute or traumatic RRI are more common in trail runners than road runners due to variability of surfaces encountered. Except for cuts and bruises, the most common acute RRI ankle sprains, specifically lateral or inversion sprains are.

- Lateral Ankle Sprain

- Pain along the outside of the ankle after rolling it (forced inversion)

- Damage or disruption to the ligaments along the outside of the ankle.

Prevention Through Strength Training

Why strength training? Having adequate strength through the legs is an important factor for the prevention of running related injuries. Our muscles have two key roles in the body. The first is to move different parts of the body, like extending the knee and plantar flexing the ankle while running. The second role is to stabilize and support our joints during motion. Therefore, weak muscles allow for inadequate joint alignment which can result in the loading of tissues that are not meant to handle the repetitive loads of running. There is evidence that muscle weakness in the hips and legs is a contributing factor to the common overuse injuries listed above. Runners who engaged in a strengthening program were less likely to develop an RRI than runners whose training did not include lower extremity strength training.

Which Exercise to Prevent Which Injury?

While there are many different exercises that one could do, the following are the ones that we have found to be effective. The exercises are listed for each injury, with a brief description of which muscles are targeted and why. There is a regression and progression to each exercise should it be too hard or too easy. All the exercises are done while standing on a single leg. That is because, during each step, a single leg must absorb all the impact from the foot strike and generate the power to propel the runner onto the next step, on the opposite leg.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome

- Muscle Group: Glutes, hamstrings

- Exercise: Single leg Romanian deadlift (RDL)

- Rational: The goal of this exercise is to strengthen the glutes (hip external rotators, abductors, extensors) and stretch the hamstrings. In doing an RDL, the hamstrings stretch as the body hinges forward at the hips. They are also are strengthened when returning to an upright position. A single leg RDL works corresponding glute muscles to prevent the pelvis from dropping to the unsupported side and subsequent loss of balance. These actions help to improve hip stability and joint alignment about the knee.

- Progression: Slow single leg step down off box.

- Regression: RDL with band around the knees. The band helps engage the glutes as they have work harder to prevent an inward knee movement.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

- Muscle Groups target: Glutes, quads, hamstrings

- Exercise: Single leg squat

- Rational: Strong glutes prevent a medial (inward) collapse of the knee (valgus stress) while quads and hamstrings reinforce the knee

- Progression: Single leg squat with a slow descent and explosive push up. The controlled descent mimics the eccentric loading in shock absorption while the explosive push builds power needed for acceleration.

- Regression: Double leg squat with a band around the knees. The band around the knees forces the glutes to work extra hard to prevent the inward knee collapse.

Achilles Tendinopathy + Plantar Fasciitis (PF)

- Muscle Group Targeted: Calves

- Exercise: Single leg calf raises from a deficit and SL calf raises with toe extension

- Rational: Ensuring that the Achilles tendon has adequate strength to act as a spring to effectively absorb impact, store the energy generated, and release said energy to help propel the body. A raise from a deficit position (heel lower than toes) increases the challenge and strengthens the tendon through the full range of the ankle joint.

- The toe extension single calf raise is for plantar fasciitis. By bringing the toes up into extension (towel under the toes) the PF is stretched and deeper calf muscles that help support the arch of the foot are recruited.

- Progression: Single leg pogo hops. An introductory plyometric that mimics the absorption and rebounding that the foot and ankle undergo during running. The toes do not need to be extended for the plyometrics.

- Regression: 2 up 1 down calf raises. Use two feet to push up onto the toes then use 1 foot to lower back down. The eccentric lowering helps to aid with mobility while helping to build strength. Add a towel under the toes to bias the deeper muscles in the calf and the PF, same as the base exercise.

Lateral Ankle Sprains

- Muscle group: Ankle stabilizers and intrinsic foot muscles

- Exercise: Single leg kettlebell around the world

- Rational: Standing on one leg while moving kettlebell around the body adds significant challenge to maintaining balance and ankle. The instability created by the kettlebell forces the muscles that stabilize the ankle to work extra hard. It also improves proprioception (knowing joint position in space is key for stability) allowing runners to stay balanced on variable surfaces.

- Progression: Stand on an unstable surface (foam squares, Bosu ball, couch cushions etc.). The unstable surface is an extra layer of challenge for the stabilizer muscles.

- Regression: Without a kettlebell, balance on a single leg with a band pulling the ankle both in and away from the body.

Exercise Parameters

How much and how often you should do these exercises will depend on your own personal training history. If you are an experienced runner or someone that has a regular workout regime, these exercises can be incorporated into your current plan. They can also be used as part of a warmup to activate the leg muscles before a run. If you are relatively new to running or have minimal strength training, then it is worth doing these exercises 3-4x/week. Try and do 3 sets of 8-10 repetitions with a weight that is challenging. At the end of the set you should feel like you can do 2-3 more reps.

This does not mean that you must use weights, body weight could be sufficient, you will need to find what works best for yourself. When you can complete the sets and reps easily with just body weight, add weight so that the exercise is challenging but doable. If maintaining balance during these exercises is difficult, some light assistance, such as holding on to a counter or back of chair, is fine to use initially. You will want to put as little weight on the assist as possible.

When to See a Physiotherapist?

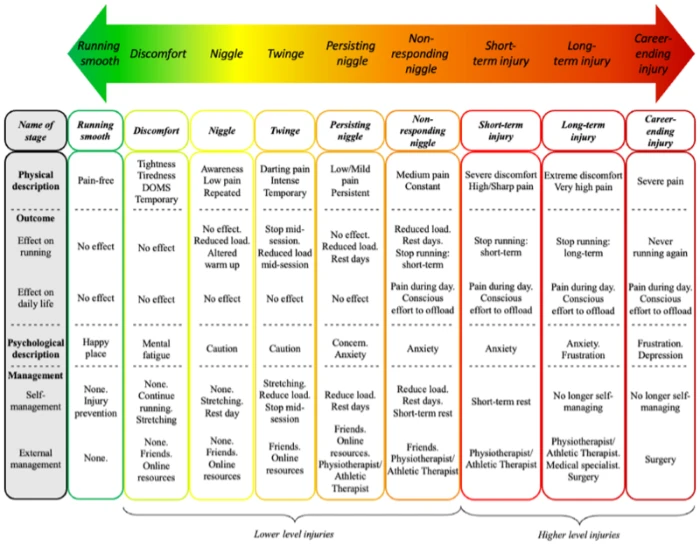

Despite the best efforts to train smartly, injuries can still happen. It is important to be able to differentiate when the injury is minor and can be successfully rehabilitated on one’s own and when it is more serious and professional help should be sought. The running injury continuum below is a helpful guide. A good time to see a physiotherapist is when the pain or issue is felt outside of a run. Another sign to get an assessment is when you feel concerned or anxious about the injury. It is best to treat injuries quickly before they become more severe and impact your quality of life.

If you are just starting your running journey or you have been experiencing recurring pain or injury while running follow the link to book a running assessment with one of our physiotherapists today!

References

Aicale, R., Tarantino, D., & Maffulli, N. (2018). Overuse injuries in sport: A comprehensive overview. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 13, 309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-1017-5

Arnold, M. J., & Moody, A. L. (2018). Common Running Injuries: Evaluation and Management. American Family Physician, 97(8), 510–516.

Baker, R. L., & Fredericson, M. (2016). Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners: Biomechanical Implications and Exercise Interventions. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 27(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2015.08.001

Baltich, J., Emery, C. A., Stefanyshyn, D., & Nigg, B. M. (2014). The effects of isolated ankle strengthening and functional balance training on strength, running mechanics, postural control and injury prevention in novice runners: Design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 15(1), 407. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-407

Desai, P., Jungmalm, J., Börjesson, M., Karlsson, J., & Grau, S. (2023). Effectiveness of an 18-week general strength and foam-rolling intervention on running-related injuries in recreational runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 33(5), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14313

Exercise for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome—Van der Heijden, RA – 2015 | Cochrane Library. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2024, from https://www-cochranelibrary-com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010387.pub2/full

Hulme, A., Nielsen, R. O., Timpka, T., Verhagen, E., & Finch, C. (2017). Risk and Protective Factors for Middle- and Long-Distance Running-Related Injury. Sports Medicine, 47(5), 869–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0636-4

Kakouris, N., Yener, N., & Fong, D. T. P. (2021). A systematic review of running-related musculoskeletal injuries in runners. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 10(5), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.04.001

Lacey, A., Whyte, E., O’Keeffe, S., O’Connor, S., Burke, A., & Moran, K. (2023). The Running Injury Continuum: A qualitative examination of recreational runners’ description and management of injury. PLOS ONE, 18(10), e0292369. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292369

Meghan Callaway Fitness Official (Director). (2019, March 1). Single Leg Balancing With Lateral Band Resistance. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pFpZiRysZ1g

Testosterone Nation (Director). (2020, July 24). Single-Leg Kettlebell Pass. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=1x3SRhseKWU

Vincent, H. K., Brownstein, M., & Vincent, K. R. (2022). Injury Prevention, Safe Training Techniques, Rehabilitation, and Return to Sport in Trail Runners. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation, 4(1), e151–e162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmr.2021.09.032