A bit about me

My name is Robyn and I am in the process of finishing the second year of my Masters of Science in Physical Therapy at the University of Alberta. I have had the pleasure of working with the staff members here at Northgate Pivotal Physiotherapy, with Lindsay Thompson as my instructor. Throughout my time here I have treated a variety of injuries. One of the common knee injuries we see is a condition called Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS). I have decided to write a blog to explain a bit about what PFPS is and what physiotherapy can do to help relieve symptoms since this condition is so common. In addition, research is showing how treatment may not always focus primarily on the knee itself, which can be counterintuitive, so I will explain a bit about why that is the case in this blog post.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) – What is it? 1,2,3

- The primary symptom is pain behind or around the knee-cap (known as the patella)

- Most common cause of pain at the front of the knee

- Often comes on gradually or can be exacerbated with a traumatic event such as a fall on the knees

- Non-traumatic causes can be intrinsic or extrinsic

- Intrinsic factors include: improper alignment of the leg or the joint

- Extrinsic factors include: type of physical activity, repetitive activity, or changes in the intensity of a physical activity

- Main aggravating factors are weight bearing activities

- Squatting

- Running

- Stairs

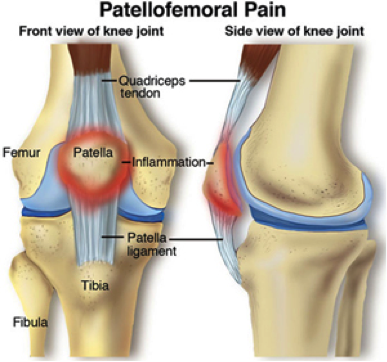

When we bend and straighten our knees, the patella glides up and down in a relatively straight line as the muscles that attach to the patella lengthen and contract (Figure 1). The gliding occurs over the big bone of our thigh called the femur. Abnormal movement or “tracking” of the patella over the femur can lead to irritation due to rubbing of the patella bone on a part of the femur bone where it does not normally contact. This can be due to imbalances (weakness/tightness) of muscles that control the movement of the patella or by imbalances of muscles that stabilize the legs to keep the legs in proper alignment which allows for normal movement. Over time, abnormal movement and rubbing of the patella on the femur can cause irritation which eventually leads to more frequent episodes of pain if not corrected and managed.

Figure 1. Depiction of the patella (kneecap) and the structures related to it. The patella is pulled upward on the femur by the patellar tendon when the knee is straightened. If the line of pull is not straight, pain can be felt in the red zone depicted in the figure.

Signs and Symptoms 1,4

- Pain in knee or knees with weight bearing activities

- Patella moves away from the midline when knee is straightened vs normally it would move up in a straight line

- Tenderness in and around the front of the knee when pressure is applied

- Cracking/clicking with knee movement (only requires treatment if painful)

- Muscle weakness in legs or hips

- Unaffected knee range of motion

- None or very little swelling

- Stiffness may or may not be reported

Who is at risk? 5,6

- Young athletic population

- Overuse or training errors such as improper form with activity

- PFPS accounts for up to 25% of all injuries in runners

- Women 2x more than men

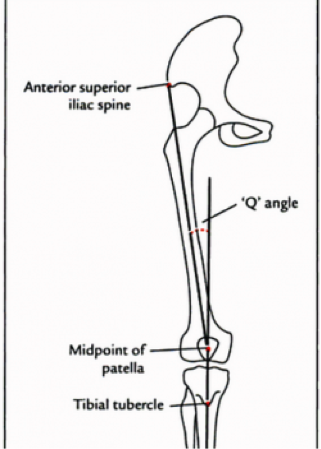

- Anatomical structure of legs – have larger Q angles

Q angle is short for quadriceps angle. The Q angle is a measure of the line of pull of the quadriceps muscles on the patella. If this angle is larger, there is a greater lateral pull on the patella. The Q angle is measured from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the middle of the patella. In women, the Q angle is generally larger since a female pelvis (hip bone) is structurally wider. Normal values in females are 13-18 degrees and larger angles increase risk of developing PFPS.

Figure 2. Depiction of the Q angle and the points of measurement to determine a Q angle.

Treatment

There is no set protocol for treating PFPS. Treatment will depend on each individual’s unique case and presentation. Based on experience and training, different therapists may also have certain techniques they use so treatment can vary between therapists. Currently, research shows a few strategies that can be effective treatment for many cases of PFPS and therefore we have been incorporating these interventions into our treatment plans for individuals diagnosed with PFPS in the clinic.

- Hip abductor strengthening 2,7

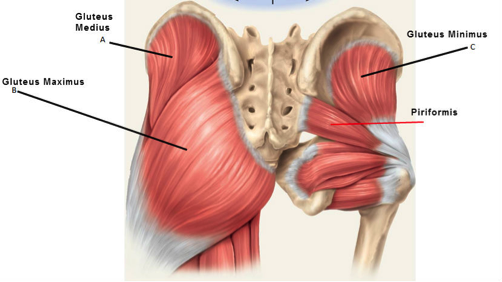

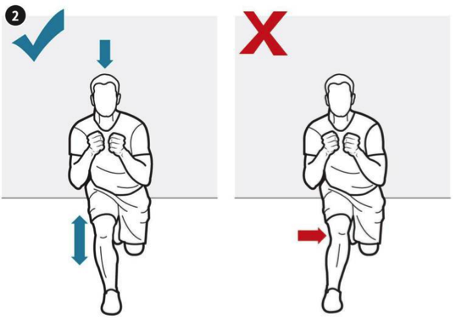

Strengthening exercises for the hip abductors in order to help combat PFPS is found to be supported by a number of recent research articles. Our hip abductors are muscles that are used to bring the leg away from the midline, for example if you were to take a step out to the side. The notable hip abductors include gluteus medius and gluteus minimus (Figure 3). These muscles also help to keep our leg in proper alignment and prevent us from forming a “dynamic Q angle”. A dynamic Q angle is when your leg forms a Q angle that is larger than when you are standing still on two feet. This can occur because of muscle weakness and is often seen in movements such as single leg squats (refer to Figure 4). Again, this incorrect alignment of the leg can cause the patella to track incorrectly and can lead to PFPS. It is very common for these muscles to be weak, even in those who do not have symptoms of PFPS, therefore this is an important part of the treatment plan of many patients but especially those who exhibit pain in their knees. As indicated by the research, strengthening of the hip abductors may also be indicated in the prevention of PFPS in patients that are at risk for the condition such as young female athletes.

Figure 3. Gluteus medius and gluteus minimus in relation to their surrounding structures. These two muscles help to abduct our hips.

Figure 4. Single leg squat. The figure on the left shows a single leg squat performed with proper form. The image on the right shows what can happen when a single leg squat is completed with weak hip abductors. In the image on the right, the knee falls inwards which means the leg is no longer straight. When the leg is not straight, it is difficult for the patella to move in a straight line up and down the leg as the knee bends and straightens.

2) Strengthening muscles around the knee 7

Overall, research shows that addressing the entire lower limb to be important in the rehabilitation of PFPS. In other words, treatment should focus on more than just the knee. Greater improvements in pain relief and knee function are shown when strengthening programs are applied to both knee and hip muscles.

The quadriceps are the muscles that attach to the patella and straighten our legs. If these muscles are not all adequately strong and working together, the patella may not track properly when the quadriceps contract. However, strengthening the quadriceps in isolation can increase force and pressure in the structures related to PFPS (patella and femur) which might further cause irritation. Exercises such as mini squats are more favourable since they help strengthen the quadriceps while also strengthening other muscles that support the hips and knees. The key with mini squats is to ensure proper form and alignment of the legs while completing the exercise otherwise the exercise could bring on symptoms in the knees.

Figure 5. Mini squat for strengthening of entire lower extremity including the quadriceps. A resistance band is often used to help cue the proper alignment of the legs (preventing an active Q angle).

3) Stretching 2,7

Another way PFPS is commonly managed is by stretching. If certain muscles are tight, they can have a direct effect in causing PFPS by pulling the patella out of alignment as it glides. Another way tight muscles have an effect on the patella is if they cause the overall alignment of the leg to be altered, leading to active Q angles or compensations with movement that put stress on certain areas of the legs more than other areas.

A therapist may choose to stretch any tight muscles manually and/or show stretches to be completed at home. The following muscles have been found to be commonly tight in those who experience PFPS:

- Hamstrings

- Iliopsoas (hip flexors)

- Tensor fascia lata

- Gastrocnemius

If one or more are tight they should be addressed as a part of the treatment plan.

4) Other Treatment 7

Due to the huge variety in patient presentation and therapist style, I will not be able to touch on everything regarding PFPS in this blog. Based on experience, therapists may add other forms of exercises and treatment such as manual therapy. Other factors that seem to play less of a role in PFPS intervention, though may still be addressed and treated include:

- foot over pronation

- generalized joint laxity

- patellar hypermobility

- limb length discrepancy.

Adjuncts to treatment 1,8

Physiotherapy should include education on the condition as well as exercises and/or manual work as a part of the treatment plan for any condition. Additionally, there are a few extra measures we can take at an appointment to assist the process or manage symptoms:

- Taping

- K-tape used to hold patella in place so it moves in proper alignment with activity

- Allows for a bit more mobility than a brace

- Helps confirm diagnosis if it reduces symptoms

- Can be done a number of different ways depending on patient preference or activity requirements

- Acupuncture

- Pain modulation

- Help manage tightness in surrounding muscles

- Modalities

- Heat, ice, TENS, etc. can all help with short term pain modulation

- Swimming vs running

- Alternative way to maintain fitness

- Less weight bearing through the knee

How do we know if the PFPS getting better? 9,10,11

Physiotherapists use something called “outcome measures” to measure an effect that a treatment is having and to determine if that effect is positive or negative. Research shows that there are two specific outcome measures that could be used to help determine the effects of treatment over time.

- Anterior Knee Pain Scale: a highly reliable scale with a specific focus on symptoms and activities associated with anterior knee pain

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS): for patient self-report of pain or symptoms

- VAS consists of rating pain or symptoms on a scale of 0-10 to help describe symptoms from a minimum (no symptoms at all) to a maximum (worst imaginable symptoms)

- A change of at least 1.1 in rating depicts that a significant difference has been made

Prognosis 12

- Patients may gradually return to sport or activity over a period of 4-6 weeks

- Increase activity as symptoms are decreased

- Exercises should be continued at home to prevent regression or return of symptoms

- Unfortunately, about 40% of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome may have long-term symptoms (>12 months)

- However, research does not clarify if these recurrent symptoms are constant, intermittent, or seldom

- Greater chance of recovery sooner if treatment is started soon after initial symptoms are experienced

- Better prognosis if symptoms are not as severe by the time treatment is initiated

- Key is for early intervention when symptoms are noticed and preventative measures in populations susceptible to PFPS

Written by: Robyn Losch MScPT Student

References

- DynaMed Plus [Internet]. Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. 1995 – . Record No. 116002, Patellofemoral pain syndrome; [updated 2016 Aug 31, cited May 23, 2017]; [about 14 screens]. Available from http://www.dynamed.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=DynaMed&id=116002. Registration and login required.

- Espí-López G, Arnal-Gómez A, Balasch-Bernat M, Inglés M. Effectiveness of Manual Therapy Combined With Physical Therapy in Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: Systematic Review. Journal Of Chiropractic Medicine [serial online]. 2017;16(2):139-146. Available from: British Library Document Supply Centre Inside Serials & Conference Proceedings, Ipswich, MA. Accessed May 31, 2017

- Petersen W, Ellermann A, Gösele-Koppenburg A, et al. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Oct;22(10):2264-74 full-text

- Lankhorst N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, van Middelkoop M. Factors associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. British Journal Of Sports Medicine [serial online]. March 2013;47(4):193-206. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Herrington L. Does the change in Q angle magnitude in unilateral stance differ when comparing asymptomatic individuals to those with patellofemoral pain?. Physical Therapy In Sport [serial online]. May 2013;14(2):94-97. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- Horton MG, Hall TL. Quadriceps Femoris Muscle Angle:Normal Values and Relationships with Gender and Selected Skeletal Measures. Phy Ther 1989; 69: 17-21.

- Halabchi F, Mazaheri R, Seif-Barghi T. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome and Modifiable Intrinsic Risk Factors; How to Assess and Address? Asian Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013;4(2):85-100.

- Campbell, S. A., Valler, A. R. (2016). The Effect of Kinesio Taping on Anterior Knee Pain Consistent With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Critically Appraised Topic. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 25(3), 288-93. doi: 10-1123/jsr.2014-0278.

- Chesworth, B., Culham, E., Tata, G., & Peat, M. (1989). Validation of outcome measures in patients with patellofemoral syndrome. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 10(8), 302-308. doi:10.2519/jospt.1989.10.8.302.

- Hawker, G. A., Mian, S., Kendzerska, T. and French, M. (2011), Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res, 63: S240–S252. doi:10.1002/acr.20543.

- Watson, C., Propps, M., Ratner, J., Zeigler, D., Horton, P., & Smith, S. (2005). Reliability and responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale and anterior knee pain scale in patients with anterior knee pain. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 35, 136-146. Retrieved from http://www.jospt.org/.

- Collins N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Crossley K, van Linschoten R, Vicenzino B, van Middelkoop M. Prognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysis. British Journal Of Sports Medicine [serial online]. March 2013;47(4):342-350. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed May 26, 2017..

Figure Sources

Figure 1: http://www.moveforwardpt.com/symptomsconditionsdetail.aspx?cid=f6dfe597-2f7d-4f1e-9aff-67694dca085f

Figure 2: http://www.physio-pedia.com/%27Q%27_Angle

Figure 3: http://corewalking.com/butt-stuff-gluteus-medius-piriformis/

Figure 4: http://drcaley.com/blog/2014/5/21/the-single-leg-squat-test

Figure 5. http://lermagazine.com/article/the-role-of-hip-strength-in-acl-rehabilitation